On a double-crop rice field in Nhon Hoa Lap commune (Tan Thanh, former Long An), Mr. Nguyen Van Dung, 52 years old, stood silently looking at the sparkling water in the afternoon sun. This year’s flood flooded the fields, but the silt was thin and there were not many fish and shrimp left.

“It’s been more than ten years since there’s been a big flood, but the benefits are no longer the same as before,” he said. His family is one of the few households that still keeps the practice of “draining the fields and living with the floods” among fields that have been completely diked to grow three-crop rice.

Once the most prosperous season of the year, floods now only make farmers more worried. The fields are no longer “bathed” with silt, fish and perch are becoming rarer, and rice farmers are not profitable. In many places, fishermen quit their jobs and children left the countryside to go to the city to make a living.

A decade of “poor flood” is changing life in the West – where people once considered water as the source of life.

Memories of “living with floods”

On the dike separating the three-crop rice fields and the two-crop rice fields that are releasing water, Mr. Dung pointed towards the vast field: “In the past, floods flooded the roofs of our houses, but our people could still survive thanks to fish and alluvium.”

Mr. Dung’s family has been a farmer for many generations. He said, in the past, Dong Thap Muoi people called August to October of the lunar calendar the flood season – water from the upstream overflowed the fields and then receded slowly, not massively like the Central and Northern regions. At that time, there were no dikes, the whole village was flooded with water, and people traveled by boat. Anyone who has lost someone in their family must wait for the flood to recede before burial; Sometimes a wooden frame is built and the coffin is kept to wait for the rainy season to pass.

“There was a flood that was a few inches away from flooding the roof. I had to cut through the roof to bring the boat in. At night, I used a rope to tie my daughter’s feet, afraid she would fall asleep and fall into the water,” Mr. Dung remembers.

But when the flood is big, people do not “fight the flood” but live by it. People look at how high the roots of Ca Na trees and Sesbania bushes grow and they know that the flood will only rise that far. Before the 1990s, farmers also planted the Truong Hung seasonal rice variety, sown from the 4th lunar month. Wherever the water level rose, the rice stalks reached there, until Tet.

There is no well water or filter yet, people just scoop water from the fields into jars, let the alum settle, then cook and drink. The fields have little fertilizer, so flood water is both a source of life and a “cleaner”.

In Mr. Dung’s memory, the flood season is a season of plenty. Early in the morning, just cast the net 50 meters into the field, half an hour later there are dozens of kilograms of ling fish and perch; One session of fishing is enough for a pot of rice. The country brought with it field vegetables – water lily, sesbania, water chives – which became Western specialties.

“That season, people lived well during three months of floating water,” he said.

Floods also bring silt, helping the fields “rest” and then revive. At the end of September, the flood subsided, people sowed the winter-spring crop, and harvested it in mid-January; Then the fields rest for a few months before the summer-autumn crop in April. When the rice has just been harvested and the water returns, people “pump and weave” simultaneously, saving costs and preparing for a new crop. In years of big floods, when the rice harvest is successful, fertilizer costs are reduced by about 30%, and pathogens and weeds are swept away by the water.

Since 2011, the floods have gradually decreased. Fields are no longer “bathed” with silt and hardened soil, fertilizer costs have increased, and rice has lost its value. Mr. Dung once switched to growing lotus, then gave it up because it withered when his neighbors sprayed it. Now that he has just over a hectare of field left, he grows jackfruit and raises cows to survive. From fish to vegetables, he now has to go to the market to buy everything.

The eldest daughter followed her husband. This year, his son also left the hometown to apply for a job. After more than a decade of being “poor”, Mr. Dung said, what he lost was more than what he kept.

The water is shallow, the fish are dry

More than a hundred kilometers from Mr. Dung’s house, Tran Vu Linh, 34 years old, and his younger brother ran on a boat to a flooded field in Binh Thanh commune (Dong Thap), close to the Cambodian border. The two brothers set out more than 100 traps – a type of trap called “twelve prison doors” because no fish can escape – but by noon, they could only get a few small loaches, a few shrimps and crabs.

“In the past, I ordered 150 batches and collected 20-30 kilograms of fish every day, but now it’s reduced tenfold,” Linh said.

Linh’s family has been a fisherman for three generations. His father, Mr. Sau Thanh, used to fish in Tonle Sap Lake (Cambodia) and then returned to Dong Thap Muoi to live in a floating house. Twenty years ago, the flood season was a time of “making good money”: snakes crawled onto the mounds, catfish and ling fish were so numerous that “the boats had to line up to buy”. Now, every day he only earns hundreds of thousands, enough money for the market.

“The river now has no fish, only water remains,” Mr. Sau said sadly.

Many professional friends have left the country to go to Binh Duong and Long An to find work. Linh said, if the water is still poor next year, he will also “retire” – ending three lifetimes working in the river.

Not only is there less silt and fish and shrimp, the flood also causes landslides and great damage in the West.

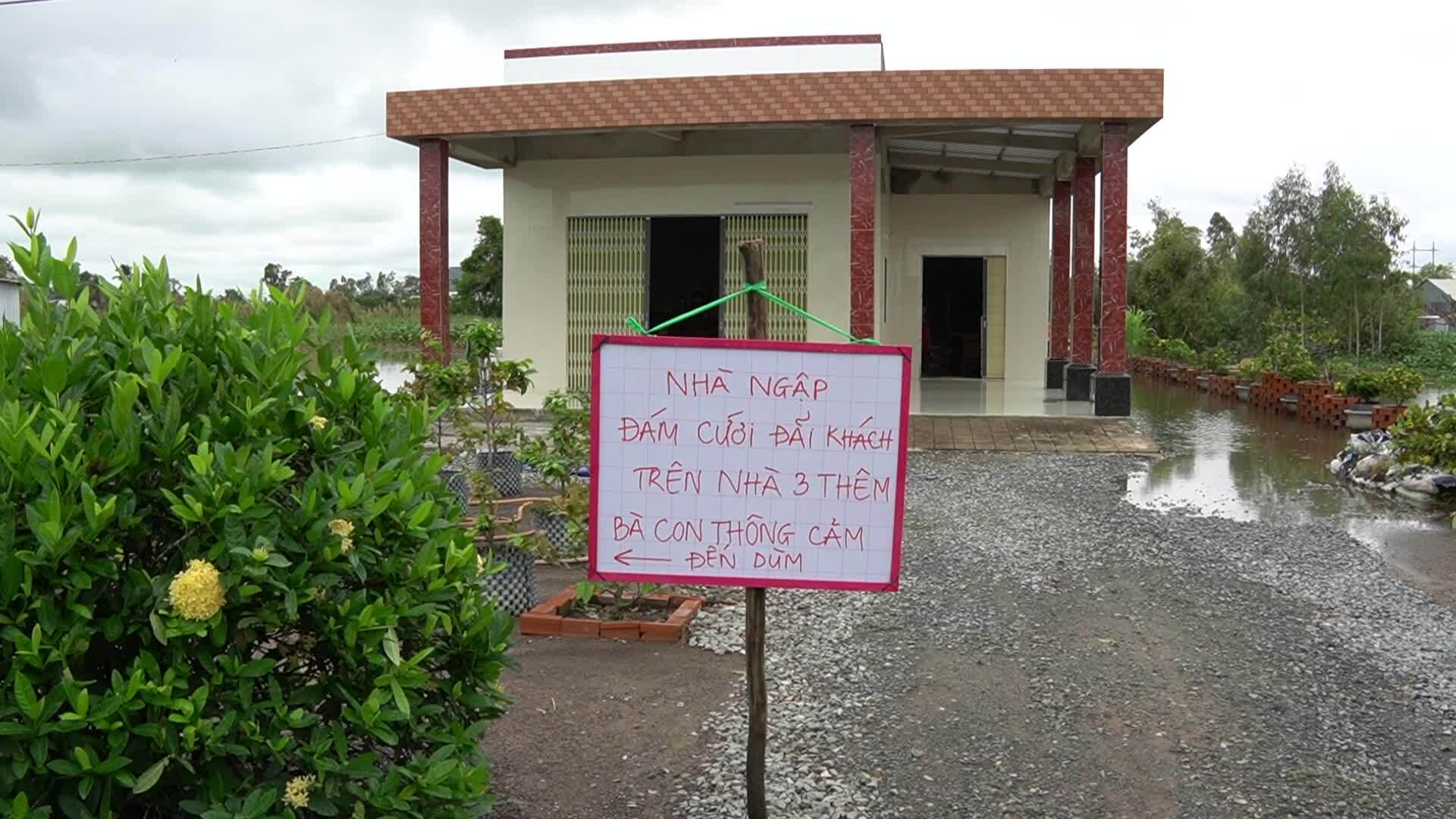

In Tan Chau (An Giang), the water level was 0.75 m higher than last year, causing 250 houses to be flooded, many roads were cut off, and people had to travel by boat.

Many important dike sections in Long An and Dong Thap broke, causing nearly 1,000 hectares of third-crop rice to be completely lost and 700 hectares of fruit trees to be damaged.

Downstream, Can Tho’s high tide peaked at 2.33 m, exceeding the historic mark of 2022, causing hundreds of households to be deeply flooded and more than 4,000 hectares of crops damaged. Vinh Long also lost more than 3,000 hectares, total damage to the entire region was about 100 billion VND.

Leave your hometown and go to another country to make a living

Master Nguyen Huu Thien, an independent research expert on the ecology of the Mekong Delta, analyzed that floods depend on upstream rainfall, which usually fluctuates 15% per year and can vary up to 30% between decades. This year, due to La Nina lasting until December, heavy rain caused floods to rise, but the water level in Tan Chau and Chau Doc is still lower than in 2000 and 2011.

“The flood is low but many places are still flooded because the center of the delta has lost water storage space,” Mr. Thien said.

Previously, each flood season from August to October of the lunar calendar, two natural flood storage areas, Long Xuyen Quadrangle and Dong Thap Muoi, could contain 9.2-10 billion m³ of water.

Over the past 30 years, the closed dyke system serving third-crop rice has caused water storage capacity to decrease sharply: Long Xuyen Quadrangle is only 4.7 billion m³, Dong Thap Muoi 6.5 billion. Previously, the tides from the sea followed seven river branches into the fields, regulating the flow. Now the dykes and sluices are closed, causing tidal water to flow straight to the center, while upstream water has no place to store it and flows downstream.

When two water sources meet in the middle of the plain, the river level rises. The garden fields are surrounded by dikes so the water cannot drain and floods into the urban area. In Can Tho, Ninh Kieu area closed the dike, water flowed to Binh Thuy. While the middle of the delta is deeply flooded, many coastal fields in the freshwater zone remain dry.

“The delta is now like a person with high blood pressure, losing blood vessels, only the aorta remains,” Mr. Thien said, comparing the floodwaters from the upstream pressing down, the tides pressing up from the sea causing “the aorta to bulge”.

According to him, floods from rivers flowing into the sea every year create moderately salty waters, rich in silt, nourishing coastal ecosystems. Thanks to that, the delta’s marine fisheries output is equivalent to the total output of the remaining regions.

Alluvium creates a layer of turbid water that covers more than 700 km of coastline, accreting the delta for 6,000 years, moving on average 16 m to the East each year, 26 m to Cape Ca Mau. When there is little silt, waves erode sandy soil, causing landslides.

Floods also provide fresh water in the dry season, balance salt and freshness, enrich nutrients for fields and gardens, and wash away alum and toxins in the soil. Lacking alluvium, the river is empty, “starving water”, filling the banks with soil, causing increased landslides.

Every high water season, hundreds of thousands of tons of white fish flood the fields, providing natural nutrients for people and the ecosystem. “The damage caused by dike breakage and rice flooding is easy to calculate in terms of money, but the benefits of flood water are huge and difficult to measure,” Mr. Thien said.

Only people in flooded areas can clearly feel these benefits. In the afternoon of early November, heavy rain caused waves to rock the floating house, so Mr. Sau and his wife had to use a winch to anchor it. After three generations of fishing, seeing his grandson studying in a solid house, he felt a little reassured.

At his advanced age and diabetes, he wanted to rest, but after dozens of “poor” seasons, life was still difficult. A few days ago, an acquaintance in Kien Giang called and invited him to go catch crabs and sea fish.

Mr. Sau said that the river has run out of fish, so he has to go to the sea – where there is still a lot of seafood – to fish. If he is frugal, he can earn nearly 100 million VND each year and send it back to his wife to build a small house to ease her hardships in her old age.

Hoang Nam

Lesson 3: ‘Gamble’ of third-crop rice